Bauchi Audit Exposes Universities, Polytechnics, Colleges, and Parastatals: How Did ₦Billions in Public Funds Go Unaccounted For, Why Were Revenues Unremitted, and Who Will Be Held Legally Responsible?

How did institutions meant to uphold discipline, transparency, and public trust become hubs of financial disorder? An audit investigation by WikkiTimes reveals widespread financial mismanagement across Bauchi State’s universities, polytechnics, colleges, hospitals, agencies, and parastatals, raising urgent questions about accountability, oversight, and the future of public finance in the state.

The Auditor-General’s report shows a consistent pattern: payments without documentation, unretired advances, missing revenue, inflated costs, forged or incomplete records, and expenditures without approval. These violations were not isolated to ministries or Government House—they extended deep into educational institutions and public agencies that are supposed to set standards in record-keeping, training, and ethical governance.

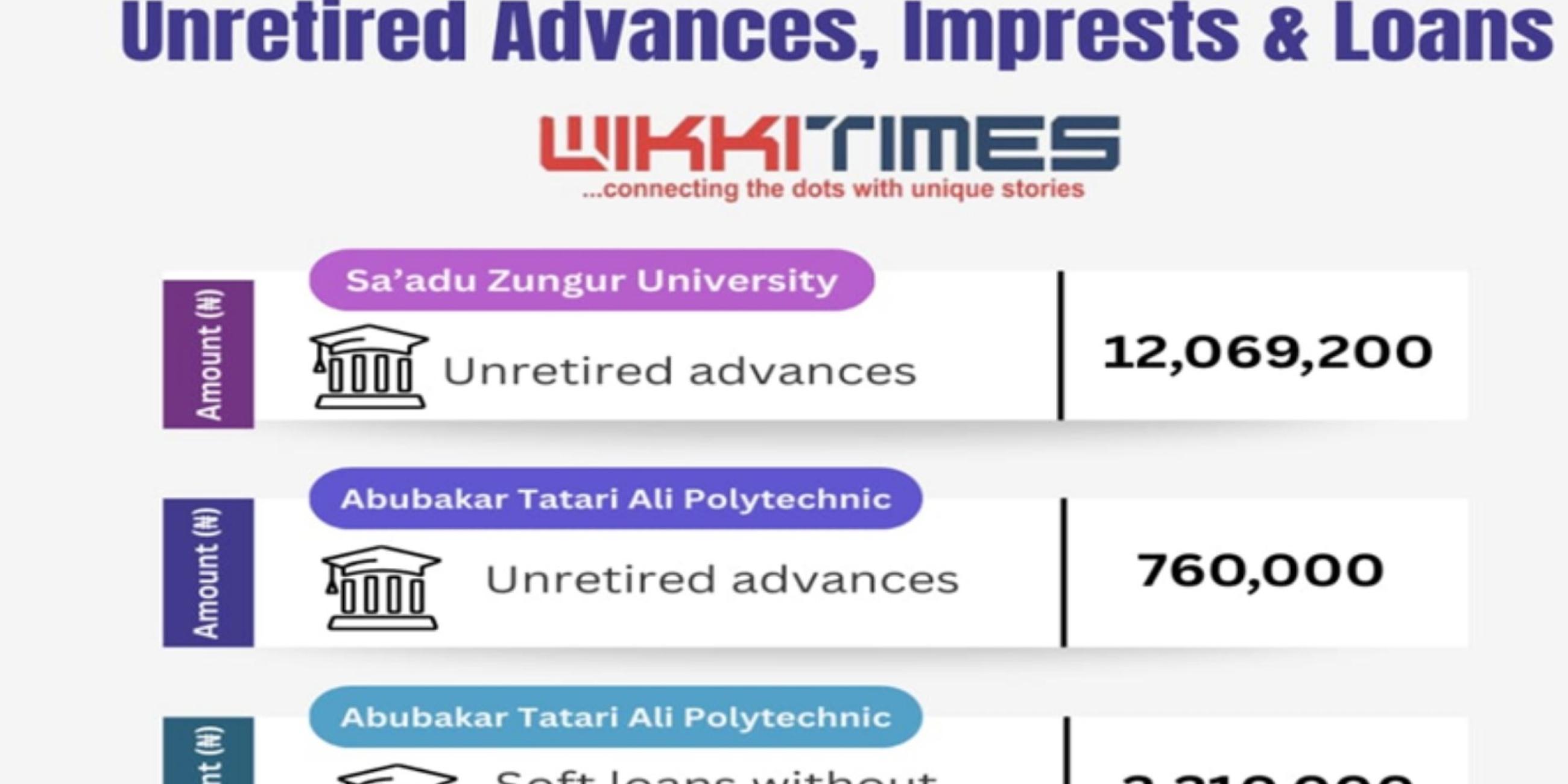

At Sa’adu Zungur University, the state’s flagship institution, auditors recorded ₦63.5 million in payments without supporting documents, ₦12 million in unretired advances, ₦48 million in vouchers not presented for audit, ₦9.1 million in receipt discrepancies, ₦14.5 million in inflated diesel costs, and ₦84.2 million in unremitted tax deductions. Another ₦101 million was not posted to the cash book, making the trail of funds impossible to trace. An institution named after a symbol of moral discipline now stands accused of systemic financial indiscipline.

At Abubakar Tatari Ali Polytechnic, auditors uncovered what they described as one of the most detailed cases of financial breakdown: ₦21.4 million in government revenue with no evidence of remittance, ₦13.4 million in undocumented payments, ₦15.1 million in vouchers withheld from audit, ₦28.6 million in store purchases not entered into ledgers, and multiple unretired advances and imprests. Additional red flags included ₦32.8 million in unauthorised payments, ₦5.7 million paid without documentation, and ₦5.2 million in soft loans without proof of recovery.

Other institutions followed the same pattern. A.D. Rufa’i College of Legal Studies recorded millions in undocumented, unauthorised, and unacknowledged payments, alongside major store ledger discrepancies—echoing earlier reports of student exploitation. At the Bill and Melinda Gates College of Health Sciences, auditors flagged bank reconciliation gaps, voucher irregularities, and cash-book discrepancies. Health agencies, including the Specialist Hospital Board and Bauchi State Health Contributory Management Agency, were cited for diesel payments without retirement records and funds disbursed without approval.

The audit further exposed revenue losses in parastatals. At Yankari Express Corporation, auditors recorded a staggering ₦165.5 million gap between revenue collected and bank lodgements, alongside missing vehicles, undocumented spare parts purchases, and multiple unsubmitted vouchers. At Yankari Game Reserve, findings included unauthorised payments, ghost beneficiaries, unaccounted revenue, undocumented diesel purchases, and unexplained bank withdrawals—suggesting deep-seated weaknesses in financial controls.

Perhaps most alarming is what did not happen. According to the audit, missing vouchers remained missing, unremitted revenue was not accounted for, advances were not recovered, and disputed sums were not refunded. Explanations submitted by institutions failed to resolve the issues, leaving large portions of public funds in limbo.

The report also outlines the legal consequences. Under the 1999 Constitution, all public spending must be authorised by law, with the Auditor-General empowered under Section 125 to refer violations to the House of Assembly. The ICPC Act criminalises abuse of office, while the EFCC Act classifies tax non-remittance and fund diversion as economic crimes—offences that remain prosecutable even after restitution.

This investigation forces urgent questions: How did so many institutions operate for years without basic financial controls? Why were revenues collected but never remitted? Who authorised payments without records? And will the ICPC, EFCC, and lawmakers move from exposure to prosecution? As billions of naira remain unaccounted for, Bauchi’s audit report is no longer just a financial document—it is a test of whether public office will finally be matched with public accountability.

Bauchi Audit Exposes Universities, Polytechnics, Colleges, and Parastatals: How Did ₦Billions in Public Funds Go Unaccounted For, Why Were Revenues Unremitted, and Who Will Be Held Legally Responsible?

How did institutions meant to uphold discipline, transparency, and public trust become hubs of financial disorder? An audit investigation by WikkiTimes reveals widespread financial mismanagement across Bauchi State’s universities, polytechnics, colleges, hospitals, agencies, and parastatals, raising urgent questions about accountability, oversight, and the future of public finance in the state.

The Auditor-General’s report shows a consistent pattern: payments without documentation, unretired advances, missing revenue, inflated costs, forged or incomplete records, and expenditures without approval. These violations were not isolated to ministries or Government House—they extended deep into educational institutions and public agencies that are supposed to set standards in record-keeping, training, and ethical governance.

At Sa’adu Zungur University, the state’s flagship institution, auditors recorded ₦63.5 million in payments without supporting documents, ₦12 million in unretired advances, ₦48 million in vouchers not presented for audit, ₦9.1 million in receipt discrepancies, ₦14.5 million in inflated diesel costs, and ₦84.2 million in unremitted tax deductions. Another ₦101 million was not posted to the cash book, making the trail of funds impossible to trace. An institution named after a symbol of moral discipline now stands accused of systemic financial indiscipline.

At Abubakar Tatari Ali Polytechnic, auditors uncovered what they described as one of the most detailed cases of financial breakdown: ₦21.4 million in government revenue with no evidence of remittance, ₦13.4 million in undocumented payments, ₦15.1 million in vouchers withheld from audit, ₦28.6 million in store purchases not entered into ledgers, and multiple unretired advances and imprests. Additional red flags included ₦32.8 million in unauthorised payments, ₦5.7 million paid without documentation, and ₦5.2 million in soft loans without proof of recovery.

Other institutions followed the same pattern. A.D. Rufa’i College of Legal Studies recorded millions in undocumented, unauthorised, and unacknowledged payments, alongside major store ledger discrepancies—echoing earlier reports of student exploitation. At the Bill and Melinda Gates College of Health Sciences, auditors flagged bank reconciliation gaps, voucher irregularities, and cash-book discrepancies. Health agencies, including the Specialist Hospital Board and Bauchi State Health Contributory Management Agency, were cited for diesel payments without retirement records and funds disbursed without approval.

The audit further exposed revenue losses in parastatals. At Yankari Express Corporation, auditors recorded a staggering ₦165.5 million gap between revenue collected and bank lodgements, alongside missing vehicles, undocumented spare parts purchases, and multiple unsubmitted vouchers. At Yankari Game Reserve, findings included unauthorised payments, ghost beneficiaries, unaccounted revenue, undocumented diesel purchases, and unexplained bank withdrawals—suggesting deep-seated weaknesses in financial controls.

Perhaps most alarming is what did not happen. According to the audit, missing vouchers remained missing, unremitted revenue was not accounted for, advances were not recovered, and disputed sums were not refunded. Explanations submitted by institutions failed to resolve the issues, leaving large portions of public funds in limbo.

The report also outlines the legal consequences. Under the 1999 Constitution, all public spending must be authorised by law, with the Auditor-General empowered under Section 125 to refer violations to the House of Assembly. The ICPC Act criminalises abuse of office, while the EFCC Act classifies tax non-remittance and fund diversion as economic crimes—offences that remain prosecutable even after restitution.

This investigation forces urgent questions: How did so many institutions operate for years without basic financial controls? Why were revenues collected but never remitted? Who authorised payments without records? And will the ICPC, EFCC, and lawmakers move from exposure to prosecution? As billions of naira remain unaccounted for, Bauchi’s audit report is no longer just a financial document—it is a test of whether public office will finally be matched with public accountability.