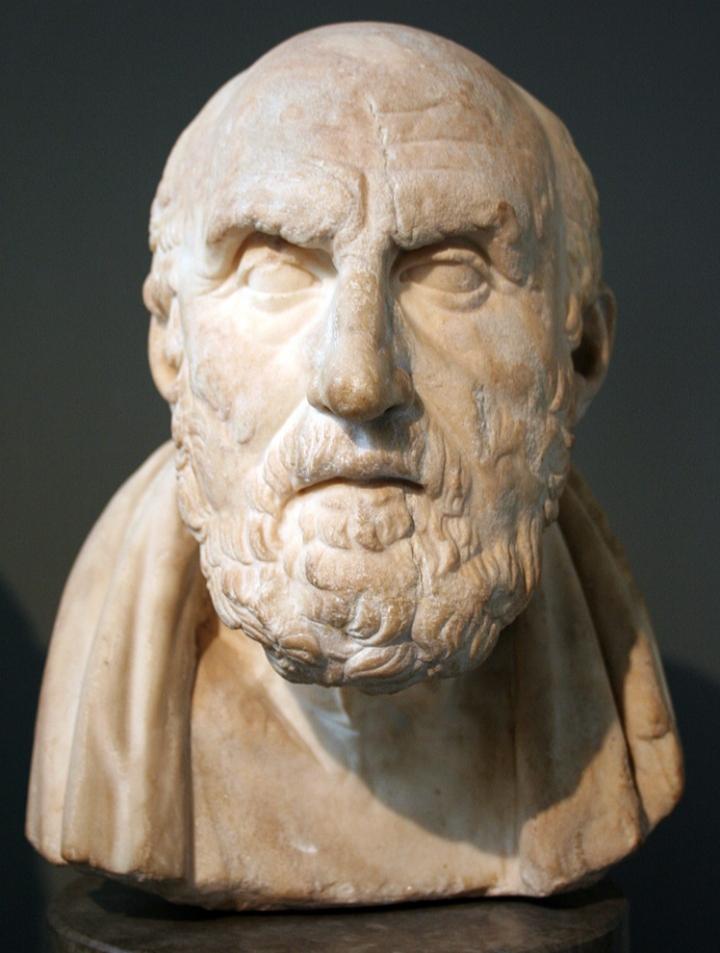

Chrysippus of Soli: The Stoic Genius Who Died Laughing at His Own Joke

Chrysippus of Soli: The Stoic Who Mastered Logic and Laughed at Fate

Introduction

Among the towering figures of ancient philosophy, few names command as much quiet authority as Chrysippus of Soli. He was not as famous in popular memory as Socrates, nor as literary as Plato, nor as widely read today as Aristotle. Yet in the world of philosophy, especially within Stoicism, Chrysippus was the architect who ensured the survival and strength of an entire school of thought.

Without him, Stoicism might have faded into obscurity after its founder. With him, it became one of the most influential philosophies in Western history, shaping Roman thought, Christian theology, Enlightenment ethics, and even modern cognitive psychology.

And yet, history remembers him not only as a master logician but also as the philosopher who reportedly died laughing at his own joke.

This is the full and deep story of his life, his work, his mind, and the strange and ironic end that turned him into legend.

Early Life in Soli

Chrysippus was born around 279 BC in Soli, a city in Cilicia, located in what is now southern Turkey. Soli was a Greek colony, and like many Hellenistic cities, it was deeply influenced by Greek culture, language, and philosophy.

His family was said to be wealthy. Some sources suggest that his father was a man of standing in the city. However, tragedy struck early in Chrysippus’ life. His family’s wealth was reportedly confiscated by the king, possibly due to political issues. This sudden loss of fortune changed the course of his life.

Instead of living comfortably as a provincial aristocrat, Chrysippus was forced to seek opportunity elsewhere. This misfortune may have been the very event that pushed him toward philosophy.

Before turning to philosophy, Chrysippus is believed to have trained as a long distance runner. This detail, though small, tells us something important about his character. Long distance running requires endurance, discipline, and mental strength. These same qualities would later define his philosophical work.

Arrival in Athens

Like many ambitious young men of his time, Chrysippus traveled to Athens, the intellectual center of the Greek world. Athens was home to multiple philosophical schools, each competing for students and influence.

There he encountered Stoicism, founded by Zeno of Citium. Zeno had established the Stoic school in the Stoa Poikile, or Painted Porch, from which the philosophy took its name.

By the time Chrysippus arrived, Zeno had already died. Leadership of the Stoic school had passed to Cleanthes. Cleanthes was respected for his moral seriousness and devotion but was not considered a powerful systematic thinker.

Chrysippus initially studied under Cleanthes. However, he was not an uncritical student. He challenged ideas, debated vigorously, and refined arguments. He was known for questioning even his own teacher’s positions.

At one point, Chrysippus reportedly said that if he had followed the crowd, he would not have become a philosopher. This shows his independent nature. He was not satisfied with repetition. He wanted precision.

The Rescue of Stoicism

After Cleanthes died around 230 BC, Chrysippus became the third head of the Stoic school.

At this moment, Stoicism was fragile. Rival schools such as the Academy and the Peripatetics attacked its doctrines. Critics pointed out inconsistencies. Opponents mocked its rigid ethics.

Chrysippus stepped in as both defender and architect.

Ancient sources credit him with writing over 700 works. While none survive intact, fragments preserved by later writers show the range and depth of his thought.

The saying circulated in antiquity that if there had been no Chrysippus, there would have been no Stoa.

This was not exaggeration. He systematized Stoic doctrine, clarified its logic, and defended it against critics. He transformed Stoicism from a set of inspiring teachings into a rigorous philosophical system.

His Contribution to Logic

Chrysippus is often called one of the greatest logicians of the ancient world. While Aristotle developed syllogistic logic, Chrysippus developed propositional logic.

Instead of focusing only on categorical statements such as all men are mortal, he analyzed conditional statements such as if it is day, then it is light.

He studied logical connectives including if then, and, or, and not. He explored paradoxes and logical puzzles. He tried to define truth conditions with precision.

In many ways, modern propositional logic resembles the foundations laid by Chrysippus more than those of Aristotle.

He also addressed famous paradoxes such as the liar paradox, which involves a statement that declares itself false. He worked tirelessly to resolve contradictions and protect Stoic reasoning from collapse.

His work on logic was not abstract play. For the Stoics, logic was necessary for ethics. One must reason correctly in order to live correctly.

Stoic Ethics and Physics

Chrysippus did not limit himself to logic. He developed Stoic ethics and physics into a coherent whole.

Stoicism teaches that the universe is governed by reason, often identified with divine logos. Everything happens according to a rational order. Fate is not chaos but structured necessity.

Chrysippus argued strongly for determinism. According to him, every event is caused by preceding events in a chain of causation stretching back to the beginning of the cosmos.

Yet he also defended moral responsibility. This was one of his most complex philosophical achievements. If everything is determined, how can humans be responsible?

Chrysippus introduced the concept of co causation. External events may be fated, but how a person responds depends on their character and reasoning. Just as a cylinder rolls when pushed because of its shape, so a person acts according to their nature when circumstances present themselves.

Thus, fate and responsibility coexist.

In ethics, Chrysippus reinforced the Stoic doctrine that virtue is the only true good. Wealth, health, reputation, and even life itself are indifferent in moral value. What matters is living in agreement with nature and reason.

He emphasized self control, rational judgment, and emotional discipline. For the Stoics, destructive emotions arise from false judgments. Correct the judgment, and the emotion loses its power.

His Personality and Teaching Style

Ancient writers describe Chrysippus as sharp, intense, and sometimes abrasive. He was confident in argument and did not shy away from debate.

He was known for quoting opponents at length before dismantling their arguments piece by piece. Some critics accused him of verbosity. Others admired his thoroughness.

He lived modestly. Unlike philosophers who sought political power or wealth, Chrysippus dedicated himself to study and teaching.

He never married, according to most accounts, though this is uncertain. He devoted his life entirely to philosophy.

Despite his intense intellectual discipline, he had a sense of humor. The story of his death suggests that he could laugh deeply, even at absurdity.

Intellectual Battles

Chrysippus faced opposition from the Academic Skeptics, especially followers of Arcesilaus and later Carneades. They argued that certainty is impossible.

Stoicism depended on the idea of kataleptic impressions, which are clear and distinct perceptions that guarantee truth.

Chrysippus defended this fiercely. Without reliable knowledge, ethical life collapses.

He also argued against Epicureans, followers of Epicurus, who believed pleasure was the highest good. Chrysippus rejected pleasure as a primary goal, insisting that virtue alone leads to true happiness.

These debates shaped Hellenistic philosophy for generations.

The Events Before His Death

By the time Chrysippus reached old age, he had spent decades writing, debating, and refining Stoicism. He lived into his seventies, which was a respectable age for the time.

Sources suggest that he was still intellectually active in his final years.

Then came the strange and memorable incident.

According to later writers such as Diogenes Laertius, Chrysippus saw a donkey eating figs. Amused, he reportedly told a servant to give the donkey some wine to wash them down.

The image of a donkey drinking wine struck him as absurdly funny. He began to laugh.

He laughed uncontrollably.

Some accounts say he died from a fit of laughter. Others suggest he suffered a stroke triggered by laughter.

Another version claims he laughed at his own joke about the donkey.

Regardless of the exact medical cause, the story became part of philosophical folklore.

The great Stoic, master of emotional control, dying from laughter.

Interpreting the Story

Was it true?

Ancient biographies often mixed fact and anecdote. The story may have been exaggerated.

Yet it is symbolically powerful.

Stoicism teaches acceptance of fate. If Chrysippus truly died laughing, it would not contradict his philosophy. Laughter itself is not condemned in Stoicism. What is condemned is irrational passion.

If he found the situation amusing and his body failed, that too was fate.

There is a strange poetic justice in the idea that a philosopher who spent his life analyzing logic and necessity met his end in spontaneous joy.

Legacy

Though none of his works survive complete, his influence endured through later Stoics such as Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius.

Roman Stoicism was built on the foundations Chrysippus laid.

His work on logic influenced later developments in philosophy. His treatment of determinism and free will continues to be studied today.

Even modern cognitive behavioral therapy echoes Stoic insights about how judgments create emotional disturbance.

Conclusion

Chrysippus of Soli was not merely a philosopher. He was the system builder of Stoicism, the defender of reason, and the architect of a worldview that has survived more than two thousand years.

He transformed a fragile school into a durable intellectual force.

He argued fiercely for logic, determinism, virtue, and moral responsibility.

And in the end, according to tradition, he died laughing at a donkey drinking wine.

Perhaps that is the perfect ending for a Stoic. A life devoted to reason, concluded with laughter at the absurd beauty of existence.

His body perished, but his system endured.

And through that endurance, Chrysippus achieved the only immortality a philosopher truly seeks.