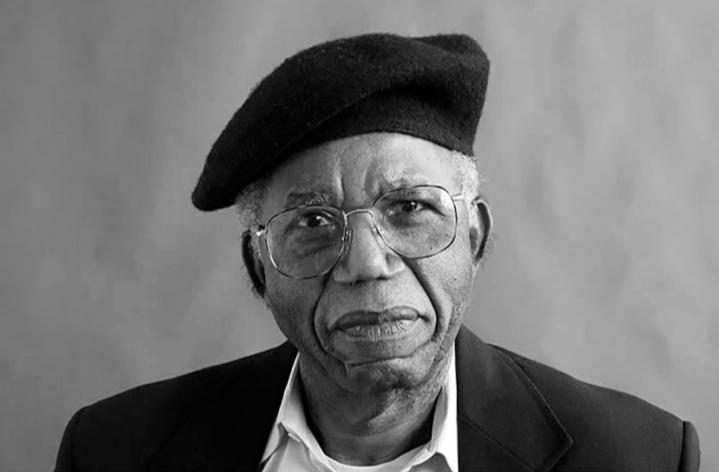

Chinua Achebe: The Storyteller Who Gave Africa Back Its Voice

Chinua Achebe

Before Africa began telling its own stories to the world in its own voice, much of its image had been shaped by outsiders. It was often portrayed as silent, primitive, or voiceless. Then came a young man from eastern Nigeria who decided to write a novel that would change everything. His name was Chinua Achebe, and with one book, he altered the course of global literature.

But his story did not begin with fame. It began in a small Igbo town under colonial rule.

A Child Between Two Worlds

Albert Chinualumogu Achebe was born on November 16, 1930, in Ogidi, in present day Anambra State, Nigeria. He was born into a Christian family. His father, Isaiah Achebe, was a catechist for the Anglican Church, and his mother, Janet, was a strong storyteller deeply rooted in Igbo tradition.

This dual influence shaped him profoundly.

On one hand, he was raised within Christianity, educated in mission schools, and taught English literature. On the other hand, he was surrounded by Igbo folktales, proverbs, songs, and rituals.

He grew up at a cultural crossroads.

Colonial Nigeria was a place of tension. British rule imposed foreign systems of governance, education, and religion. Traditional beliefs were often dismissed as inferior.

Young Achebe observed this cultural collision carefully.

He listened to elders tell stories under moonlight. He also read English classics in school. He absorbed both worlds and began quietly asking himself: Who gets to tell the story?

Education and Awakening

Achebe attended Government College Umuahia, one of Nigeria’s most prestigious schools. It was often called the “Eton of the East.” There, he excelled academically and developed a deep love for literature.

He later attended University College Ibadan, originally intending to study medicine. But literature pulled him in a different direction.

While studying English, History, and Theology, he encountered European writers like Joseph Conrad. In particular, Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness disturbed him.

He noticed how Africa was depicted as a dark, primitive backdrop for European adventure.

Achebe realized something powerful.

If Africans did not tell their own stories, others would tell them incorrectly.

The Birth of Things Fall Apart

In the mid 1950s, while working for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service, Achebe began writing the novel that would transform African literature: Things Fall Apart.

He wrote about pre colonial Igbo society. He wrote about rituals, farming seasons, proverbs, wrestling matches, and village councils. He wrote about complexity.

The protagonist, Okonkwo, was not a caricature. He was flawed, proud, strong, and human.

When Things Fall Apart was published in 1958, it shattered stereotypes.

For the first time, millions of readers around the world encountered African society through an African lens.

The novel became one of the most widely read books in world literature. It has been translated into dozens of languages and sold millions of copies.

Achebe was only 28 years old.

Writing a Nation’s Story

Achebe did not stop at one novel.

He followed Things Fall Apart with No Longer at Ease, Arrow of God, and A Man of the People. Together, these works traced Nigeria’s journey from traditional society through colonialism to independence and political corruption.

His writing was deceptively simple. Clear sentences. Direct dialogue. Yet beneath that simplicity lay deep political commentary.

He did not shout in his prose. He observed.

He believed that literature could restore dignity to a people misrepresented for generations.

The Nigerian Civil War

In 1967, Nigeria plunged into civil war after the southeastern region declared itself Biafra.

Achebe, being Igbo, supported Biafra’s cause. He served as a cultural ambassador, traveling internationally to advocate for recognition and aid.

The war was devastating. Millions died from starvation and violence.

Achebe witnessed suffering firsthand. The war deeply scarred him.

After Biafra’s defeat in 1970, he returned to a united but fractured Nigeria.

His later works reflected disillusionment with political leadership and corruption.

A Voice Beyond Fiction

Achebe was not only a novelist. He was an essayist and critic.

In 1975, he delivered a famous lecture criticizing Joseph Conrad’s portrayal of Africa. He argued that Conrad was a racist who denied Africans humanity.

The lecture sparked global debate.

Achebe was no longer just a storyteller. He was a moral voice in global literature.

Teaching and Global Influence

Achebe spent many years teaching at universities in Nigeria and abroad. He later moved to the United States after surviving a car accident in 1990 that left him paralyzed from the waist down.

Despite physical challenges, he continued writing and teaching.

He mentored young African writers, including figures like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who often cited him as a major influence.

His influence extended beyond Africa. He reshaped postcolonial studies and global literary discourse.

Themes That Defined His Work

Achebe’s writing revolved around:

Cultural identity

Colonial impact

Political corruption

Tradition versus change

The dignity of African society

He refused to romanticize Africa. He acknowledged flaws within traditional systems. But he demanded respect.

Recognition and Awards

Throughout his life, Achebe received numerous awards, including the Man Booker International Prize in 2007.

Though often mentioned as a potential Nobel laureate, he never received it.

Yet his impact arguably surpassed awards.

Things Fall Apart remains one of the most taught novels worldwide.

The Final Years

Chinua Achebe passed away on March 21, 2013, in Boston, United States.

Tributes poured in from across the globe.

He was remembered not just as a writer, but as the father of modern African literature.

The Meaning of His Story

From a boy in Ogidi listening to Igbo folktales to a global literary giant, Chinua Achebe’s journey was one of reclamation.

He reclaimed narrative power.

He proved that African stories did not need European validation to matter.

He gave Africa back its voice.

Chinua Achebe once said, “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

He became that historian.

And through his pen, the lion finally spoke.