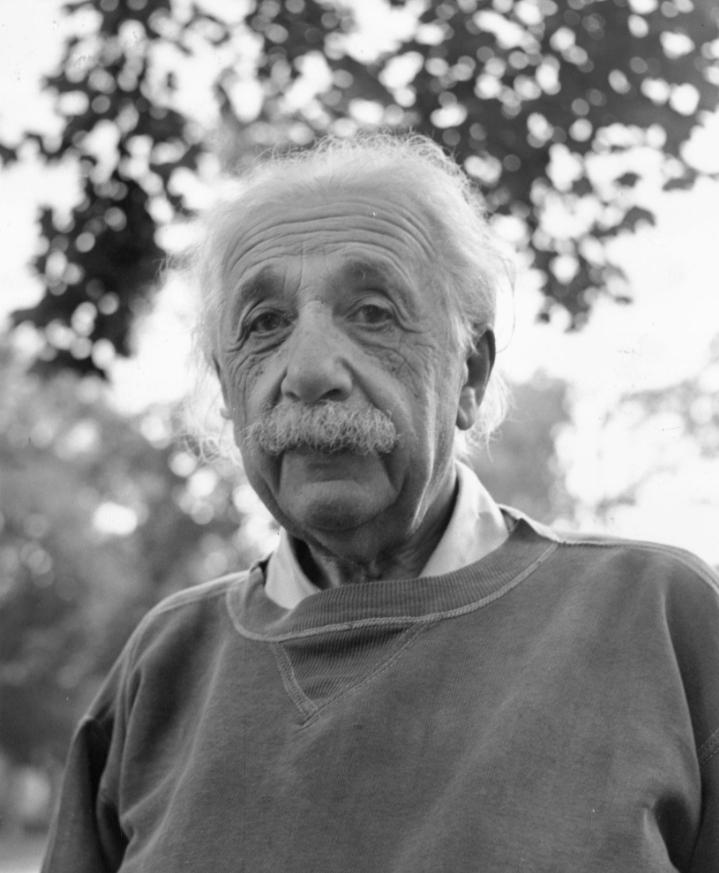

Albert Einstein: The Reluctant Genius Who Changed Time, Challenged War, and Faced the Atomic Age

Albert Einstein: The Mind That Remade Time and the Man Behind the Myth

Albert Einstein is often treated like a symbol more than a human being. His name has become shorthand for genius, and his face, especially in old age, is used to represent pure intelligence. But the real Einstein lived a life full of ambition, doubt, stubbornness, tenderness, mistakes, political conflict, family heartbreak, and exhausting work that never truly stopped. He was not born famous. He did not start as a respected professor. For years he was an outsider, a young man with an unconventional style who struggled to fit the academic mold, argued with authority, and built his greatest ideas while working a regular job.

His story begins in a Europe shaped by nationalism and industrial change and ends in America during the atomic age, where his fame was immense and his worries were heavy. What follows is a deep and complete narrative of his life, including the parts that are often smoothed over, and the events leading up to his death.

Childhood and family roots

Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg, part of the German Empire. His parents were Hermann Einstein and Pauline Koch. The family was Jewish, though not strictly religious in daily practice, and they moved relatively soon after Albert’s birth to Munich, where Hermann and his brother ran an electrical engineering business.

As a child, Einstein was observant and intense. Popular legends claim he did not speak until very late, but the reliable picture is simpler: he developed at his own pace, spoke thoughtfully, and showed an early tendency to think deeply rather than quickly. He could be quiet, even stubborn, and he disliked rote learning and strict discipline. Those traits later became part of his strength, but as a student they created friction.

One of the most important elements of his early formation was his fascination with how nature works. Stories from his childhood describe the impact of seeing a compass, the mysterious way the needle kept pointing north, suggesting unseen forces shaping the world. Whether or not every detail of those stories is perfect, the theme fits the Einstein who later wrote about wonder as the engine of science.

School, rebellion, and the search for freedom

Einstein attended school in Munich, including the Luitpold Gymnasium, where the strict educational system did not suit him. He disliked memorization and military style discipline. His personality leaned toward independence, and he often argued with teachers or withdrew from subjects that felt meaningless.

In the mid to late 1890s his family’s business struggled. They moved to Italy, leaving Albert behind in Munich for a time to finish school. He soon followed them, leaving Germany and eventually renouncing his German citizenship as a young man. He later pursued admission to the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich, today known as ETH Zurich. His first attempt did not go smoothly, but he was encouraged to complete preparatory study in Switzerland. He attended school in Aarau, where the education was more open and creative. It was there that his imagination about light, motion, and time matured.

In 1896 he entered the Zurich Polytechnic. There he trained in physics and mathematics, though he did not always attend classes in a traditional way. He relied on self study and selective focus. This habit, skipping what he found unhelpful and going straight to what mattered, later defined his approach as a scientist.

Mileva Marić, love, partnership, and the hidden pain

At Zurich he met Mileva Marić, a Serbian student in physics and mathematics, one of the few women in that environment. Their relationship grew through shared intellectual interest and emotional intensity. They exchanged letters filled with affection and scientific discussion. Later debates about how much Mileva contributed to Einstein’s early work have continued for decades, but what is certain is that they were close, and the relationship shaped both of them.

Before they married, Mileva became pregnant. Their first child, a daughter known by the nickname Lieserl, was born in 1902. The most honest answer about what happened to her is that historians do not know with certainty. Evidence from letters shows her existence, but the record of her fate is unclear, with possibilities including adoption or death in infancy. The lack of documentation has left a painful shadow over Einstein’s private life, because it reflects how fragile and socially risky their situation was at the time.

The Guardian

Einstein and Mileva married in 1903. They later had two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard. Family life, however, was never simple. Einstein’s career pressures, his emotional distance at times, and his later affairs tore at the marriage.

The patent office years and the miracle of 1905

Einstein struggled to secure an academic job after graduation. He eventually found stable employment at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. This period is crucial because it shows that revolutionary science can come from outside elite institutions. In the patent office, he examined inventions and technical claims, training his mind to test logic, isolate assumptions, and see what truly follows from what.

In 1905, while still working as a patent clerk, he produced a set of papers that changed physics permanently. These are often called his annus mirabilis papers, his miracle year.

He wrote on the photoelectric effect, proposing that light behaves in discrete quanta in ways that explained experimental results. He wrote on Brownian motion, providing strong support for the reality of atoms by linking visible particle motion to molecular behavior. He developed special relativity, reshaping the relationship between space and time by insisting that the speed of light is constant for all observers and that time and length depend on motion. He also published the short work that introduced mass energy equivalence, commonly expressed as E equals m c squared, expressing a deep unity between matter and energy.

Research Guides

These were not just clever ideas. They were radical redefinitions of basic concepts, and they arrived from a young man who did not hold a university chair. Fame did not come instantly, but recognition started to grow, and the academic world could not ignore him for long.

Academic rise, Berlin, and the collapse of a marriage

In the years after 1905, Einstein moved into academic positions in Switzerland and then in Prague, eventually returning to Zurich. His reputation rose quickly, and by 1914 he was invited to Berlin, a major scientific center, offered a prestigious position and membership in the Prussian Academy.

Berlin also marked a turning point in his personal life. His marriage to Mileva was deteriorating. The move intensified conflict, and Mileva returned to Zurich with their children. They lived apart for years.

During this period, Einstein began a relationship with Elsa Löwenthal, who was both his cousin and later his second wife. The overlap between relationships and the emotional cost of separation from Mileva were part of the private reality behind his public success.

Einstein and Mileva divorced in February 1919. The divorce settlement included an arrangement tied to the possibility of a Nobel Prize, reflecting how even his personal life was entangled with the unpredictable future of his science. He married Elsa later in 1919.

General relativity and worldwide fame

Einstein’s next great achievement, developed over years of intense work, was general relativity. Completed in 1915, it extended relativity to include gravity, describing gravity not as a simple force but as the curvature of spacetime produced by mass and energy. This theory was mathematically demanding and conceptually shocking.

The moment that transformed him into a global celebrity came when observational results during a solar eclipse supported predictions about the bending of light by the sun’s gravity. Newspapers around the world celebrated him as a genius who had rewritten the cosmos. From that point, Einstein’s public image grew larger than life.

Fame brought opportunity, but it also brought intrusion. He became a magnet for journalists, admirers, critics, and people selling nonsense. Elsa played an important role as his gatekeeper, protecting him from constant interruptions as much as possible.

Nobel Prize and what it was actually for

Many people assume Einstein won the Nobel Prize for relativity. He did not. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1921, and he received it in 1922, specifically citing his work on theoretical physics and especially the law of the photoelectric effect.

This detail matters because it reveals how the scientific community of the time viewed relativity with caution, even as it gained support. Einstein’s quantum ideas, ironically, were the ones officially honored, even though he later became famous for criticizing certain interpretations of quantum mechanics.

Politics, Zionism, pacifism, and the storm of the age

Einstein lived through an era of extreme nationalism, world war, and rising antisemitism. He spoke publicly for internationalism and against militarism. His Jewish identity became more central in his public life as antisemitism grew, and he supported cultural and educational Zionism, especially efforts connected to building intellectual institutions such as the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which later became the home of his archives.

When the Nazis rose to power in 1933, Einstein, who had been living partly abroad, did not return to Germany. He resigned from the Prussian Academy and emigrated to the United States. He and Elsa settled in Princeton, New Jersey, where he worked at the Institute for Advanced Study.

In America, his politics and outspoken views drew suspicion during the era of intense anti communist anxiety. The FBI maintained records on him and expressed concern about his politics and associations. The existence of extensive FBI interest is not a rumor, it is documented by the bureau’s own released files.

The atomic bomb, warning letters, and moral conflict

Einstein is often described as the father of the atomic bomb. That is misleading. The bomb was built by many scientists and engineers, and Einstein did not work on the Manhattan Project. However, his equation linking mass and energy helped make nuclear energy conceptually understood, and his public stature played a role in the political story.

In 1939, Einstein signed a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt warning that Nazi Germany might develop powerful new weapons based on uranium research. The letter urged the United States to take the possibility seriously. This moment later became a source of deep regret for him, because the war ended with atomic bombs used against Japan, and the world entered an era of nuclear terror.

After the war, Einstein became an advocate for nuclear arms control and international cooperation. His moral stance was shaped by the belief that science without ethical responsibility is dangerous. His celebrity made him a powerful voice, even when politicians preferred him to stay quiet.

Family tragedy and the price of genius

Einstein’s family life carried deep sorrow. His son Eduard suffered severe mental illness as a young man and spent much of his life in psychiatric care in Zurich. The emotional strain on Mileva was immense, and Einstein, living far away, could not repair what distance and earlier conflict had damaged. This part of his life is often mentioned briefly, but it mattered because it shows the limits of his ability to solve human problems compared with scientific ones.

His relationships also included behavior that many readers find uncomfortable. Historical sources show that he had affairs and romantic entanglements even while married, and later collections of correspondence revealed a complex private life that did not match the tidy saintly image some people want. A truthful biography does not hide that. It places it in context without excusing harm.

Elsa, who had supported him and shielded him from chaos, became seriously ill and died in December 1936. Einstein was devastated, and the loneliness of his later years deepened, even as his fame grew.

The later scientific years and the fight with quantum uncertainty

In his later career, Einstein continued to work on fundamental physics, searching for a unified field theory that would connect gravity and electromagnetism within one framework. He did not succeed, but his persistence showed his character: he was willing to spend years chasing a vision because he believed nature must have a deeper unity.

At the same time, he became famous for his objections to the dominant interpretation of quantum mechanics. He accepted that quantum theory worked, but he resisted the idea that randomness was a final truth about reality. His debates with other physicists were not petty. They were philosophical struggles about what science is allowed to claim about the world.

The offer to lead Israel and his refusal

In 1952, after the death of Israel’s first president, Einstein was approached about the possibility of becoming president of Israel. He declined, explaining that he lacked the natural ability and experience to deal with human beings in that political way. This episode has been documented in reputable historical accounts and remains one of the most striking examples of his self awareness about what fame does and does not qualify a person to do.

Illness, the 1948 surgery, and the final months

Einstein’s health declined in the late 1940s and early 1950s. In 1948, he underwent surgery related to an abdominal aortic aneurysm, and the surgeon Rudolph Nissen used a technique involving wrapping the weakened area to induce protective tissue response, extending Einstein’s life for several years.

By April 1955, Einstein experienced internal bleeding caused by the rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He refused further surgery, expressing that he did not want life prolonged artificially and that it was time to go.

One of the most moving details about his final hours is that he continued to think and work nearly to the end. He brought with him a draft of a speech he was preparing for a television appearance connected to Israel’s seventh anniversary, but he did not live to complete it.

He died on April 18, 1955, in Princeton Hospital at age seventy six.

After his death, the pathologist Thomas Stoltz Harvey removed Einstein’s brain during the autopsy for preservation, an act that later became controversial, especially because it was done without clear prior permission from the family at the time. Einstein’s body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at an undisclosed location.

What his life really means

It is easy to reduce Einstein to a few symbols: wild hair, a simple equation, a word like relativity. But the full story is richer and more human.

He was a child who resisted authority and pursued wonder. He was a young man who struggled for a place in academia and built a new universe from a modest office job. He was a husband whose emotional choices caused pain and whose private life was complicated. He was a father whose family faced tragedy. He was a refugee from fascism, a public moral voice in a dangerous political century, and a scientist who helped open the door to both astonishing progress and terrifying weapons.

He remained, to the end, a person who believed the universe is intelligible, and that human beings must be responsible for what they do with knowledge. The final image of him is not just of a genius dying quietly in a hospital, but of a man still drafting words, still thinking, still trying to speak to the world one more time, and then choosing to let nature take its course.