Nelson Mandela: The Long Walk from Prisoner to President

Nelson Mandela

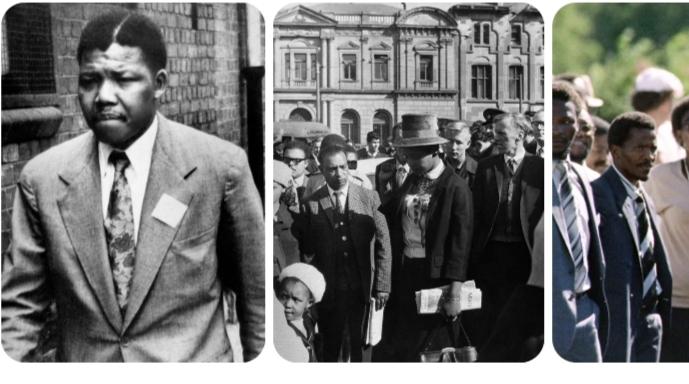

There are some lives that seem too powerful to belong to one man alone. The life of Nelson Mandela is one of those stories. It is a story of pain and courage, of anger transformed into forgiveness, of a prisoner who walked out of jail not with revenge in his heart but with a dream of unity. His journey from a rural village boy to the first Black president of South Africa is one of the most remarkable stories of the twentieth century.

A Child of Thembu Royalty

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, in the small village of Mvezo in the Transkei region of South Africa. His birth name, Rolihlahla, in the Xhosa language, meant “pulling the branch of a tree” or more simply, “troublemaker.” It would prove prophetic.

Mandela was born into the Thembu royal family. His father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, was a local chief and counselor to the Thembu king. Though not wealthy by Western standards, the family carried dignity and respect within their community. Mandela’s early life was shaped by traditional African customs, storytelling, and a deep sense of belonging to his people.

When he was about seven years old, Mandela became the first in his family to attend school. On his first day, his teacher, following colonial custom, gave him an English name: Nelson. It was common practice, but symbolic of the world he was stepping into — a world shaped by colonial power.

Tragedy struck early. Mandela’s father died when he was only nine years old. Following his father’s death, Mandela was adopted by Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, the acting regent of the Thembu people. This move changed his life. At the Great Place in Mqhekezweni, Mandela observed leadership up close. He listened as tribal elders debated issues with wisdom and patience. Decisions were made collectively, not by force. It was here that young Mandela learned that true leadership meant listening first.

Education and Awakening

Mandela later attended Clarkebury Boarding Institute and then Healdtown, a Methodist college. These schools introduced him to Western ideas, Christianity, and African nationalism. He excelled academically and eventually enrolled at the University College of Fort Hare, one of the few institutions of higher learning open to Black Africans at the time.

Fort Hare was a turning point. There, Mandela encountered students who were beginning to question the injustices of racial segregation. When he joined a student protest against university policies, he was expelled. It was his first act of defiance.

Upon returning home, Mandela discovered that the regent had arranged a marriage for him. Unwilling to accept a life he had not chosen, Mandela fled to Johannesburg in 1941. That decision marked the true beginning of his political awakening.

Johannesburg: The Fire Within

Johannesburg was a different world — loud, unequal, alive with struggle. Mandela worked as a security guard and later as a law clerk while completing his law degree through correspondence at the University of South Africa and later studying at the University of the Witwatersrand.

It was in Johannesburg that Mandela witnessed the brutal realities of apartheid — the system of institutionalized racial segregation that denied Black South Africans basic rights. Pass laws restricted movement. Land ownership was limited. Political power was entirely in white hands.

In 1944, Mandela joined the African National Congress and helped form its Youth League. Alongside leaders like Oliver Tambo and Walter Sisulu, Mandela pushed for a more radical approach against apartheid. They believed that polite appeals were no longer enough.

In 1952, Mandela and Oliver Tambo opened South Africa’s first Black law firm. The firm provided legal assistance to those harassed or arrested under apartheid laws. Every day, Mandela saw how the system crushed lives. His anger grew — but so did his discipline.

Defiance and Treason

Mandela became a leading figure in the Defiance Campaign of 1952, encouraging peaceful resistance against unjust laws. For his activism, he was arrested and banned from attending gatherings. Still, he persisted.

In 1955, the Congress of the People adopted the Freedom Charter, declaring that South Africa belonged to all who lived in it, Black and white. The apartheid government responded with fear.

In 1956, Mandela and 155 others were arrested and charged with treason. The Treason Trial dragged on for four years before they were acquitted. Though exhausting, the trial strengthened bonds among activists and deepened Mandela’s resolve.

From Peace to Armed Struggle

The Sharpeville Massacre of 1960 changed everything. Police opened fire on peaceful protesters, killing 69 people. The government banned the ANC. Mandela concluded that nonviolent protest alone would not end apartheid.

He helped form Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC. Their mission was sabotage, not terrorism. They targeted infrastructure to avoid loss of life. Mandela traveled secretly across Africa and to London to gain support and training.

In 1962, he was arrested and sentenced to five years in prison. In 1963, police raided a hideout in Rivonia and arrested several ANC leaders. Mandela was brought back to stand trial in what became known as the Rivonia Trial.

Facing the death penalty, Mandela delivered one of the most powerful speeches in history. He declared that he had fought against white domination and Black domination and cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society. It was an ideal, he said, for which he was prepared to die.

He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Robben Island: The Long Darkness

Mandela was sent to Robben Island, a bleak prison off the coast of Cape Town. He was given prisoner number 466/64. Conditions were harsh. Prisoners performed hard labor in limestone quarries. They slept on thin mats. Letters were censored. Visits were rare.

Yet even in prison, Mandela remained a leader. He encouraged fellow inmates to study, debate, and maintain discipline. Robben Island became known as the “University of Robben Island” because of the political discussions that took place.

Mandela endured 27 years in prison. Over time, he evolved. The anger of youth softened into wisdom. He studied Afrikaans to understand his oppressors. He learned that to defeat an enemy, one must understand him.

International pressure mounted. The slogan “Free Nelson Mandela” echoed around the world. Musicians, governments, and activists demanded his release.

Freedom at Last

On February 11, 1990, after secret negotiations and growing unrest, President F.W. de Klerk announced Mandela’s release. When Mandela walked out of Victor Verster Prison hand in hand with his wife Winnie, the world watched.

He could have called for revenge. Instead, he called for reconciliation.

Mandela began negotiations with de Klerk to dismantle apartheid. The process was tense and often violent. But Mandela insisted on peace.

In 1994, South Africa held its first fully democratic election. Long lines of voters waited patiently. For the first time, Black South Africans could vote.

Mandela won by a landslide.

On May 10, 1994, he was inaugurated as South Africa’s first Black president.

President of a Divided Nation

As president, Mandela focused on healing. He formed a Government of National Unity. He supported the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, allowing victims and perpetrators to confront the past.

He understood symbolism. During the 1995 Rugby World Cup, he wore the jersey of the national team — once a symbol of white dominance — and united the country behind a shared victory.

Mandela served only one term, stepping down in 1999. He believed leadership was not about holding power but knowing when to let go.

Final Years and Legacy

After retiring, Mandela continued humanitarian work through the Nelson Mandela Foundation. He focused on HIV/AIDS awareness, poverty reduction, and peace.

On December 5, 2013, Nelson Mandela died at the age of 95. The world mourned.

His life remains a testament to resilience. He taught that courage is not the absence of fear, but triumph over it. He showed that forgiveness is not weakness, but strength.

Mandela once said, “It always seems impossible until it’s done.”

From a rural boy called Rolihlahla to a global icon of peace, Nelson Mandela’s journey proves that one life, guided by principle and patience, can transform a nation.